I recently watched that 1984 Roger Donaldson masterpiece featuring la crème de la crème of the last 40-80 years’ worth of stardom.

I am talking of course about The Bounty movie featuring the likes of Sir Laurence Olivier, Edward Fox, Anthony Hopkins, Daniel-Day Lewis, Mel Gibson, Liam Neeson, and many others unknown then, now well-known silver screen habituals.

The plot of this flick is simple yet elegant.

In 1787, on the eve of a Revolution that would liberate the old continent from under the yoke of lingering medieval monarchies who had not gotten the memo their time had come, a British sloop, the Bounty, is sent to Tahiti, on a mission to find, retrieve, and transport breadfruit plants to the British West Indies (i.e., Caribbean).

Under the watchful eye of her commander, Lt. Bligh, played to a tee by the consummate Anthony Hopkins, and that of her master Fryer, played by Daniel-Day Lewis, the crew sails the ship to Tahiti. There, one of her lieutenants, Fletcher Christian, played by a shining Mel Gibson, falls in love with the Tahitian king’s daughter. Discipline falls overboard, with the crew fraternizing with the locals and starting to adopt their customs, under the severe and judging eye of their captain.

When the captain decides to cut the journey short, and starts to abuse and mistreat them, the crew rebels, mutinies, throws the captain and its followers into a longboat, with Fletcher Christian assuming command of the mutinous sailors.

While some decide to stay in Tahiti, a small party, their Tahitian female companions, and a few male natives decide to chance it on the open sea, hoping to escape the Royal Navy’s retribution.

Eventually they reach the insufficiently charted safehaven of Pitcairn Island, where they unload the cargo and burn the ship down.

This is the point where the movie leaves off… and history takes over.

It turns out that those mutineers left behind in Tahiti were apprehended by the British Navy and dealt with in the usual way: hangman’s noose. Nothing extraordinary here, eh.

What is interesting though is the fate of the people led by Fletcher Christian on Pitcairn Island.

Contrary to the popular belief that they happily lived ever after, that group had a most circuitous journey. While their descendants continue to thrive on both Pitcairn and Norfolk islands, it is what happened immediately after 1789 that captured my attention.

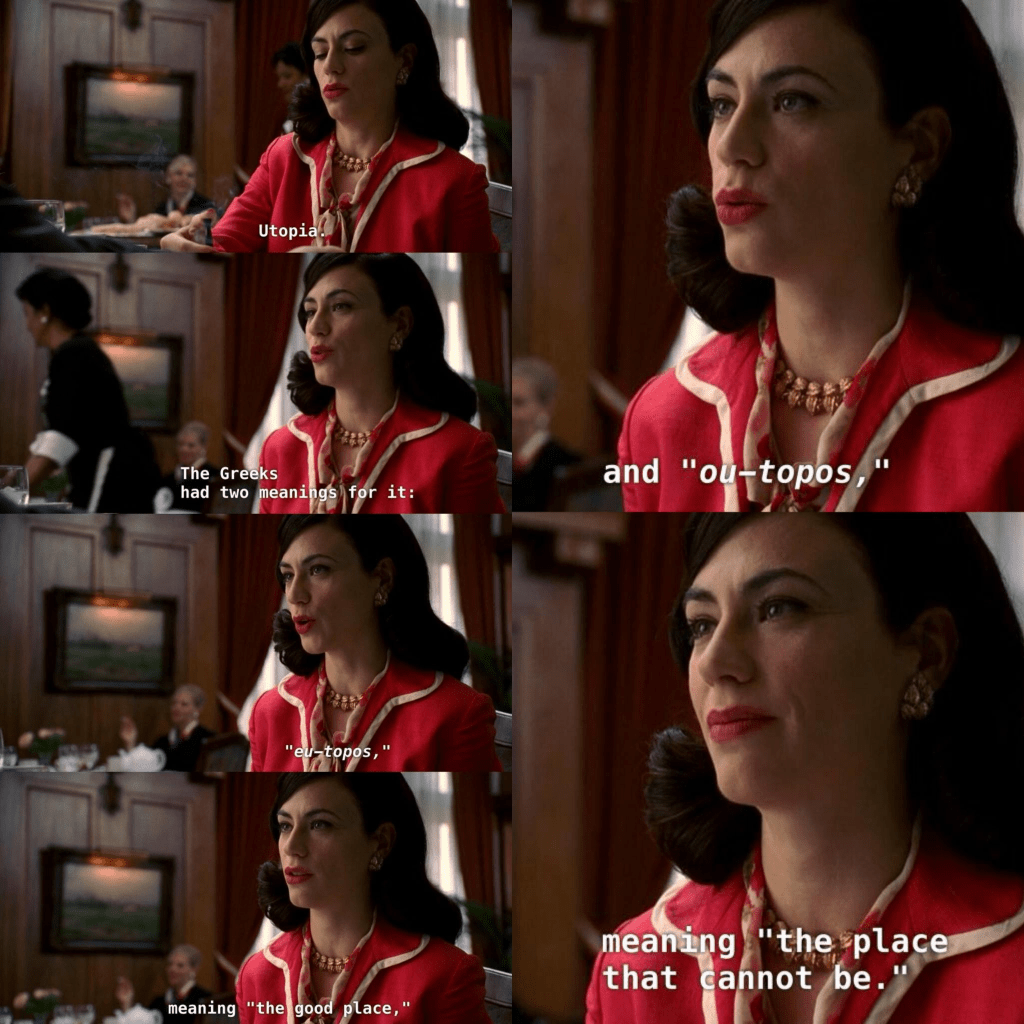

Instead of founding the utopian dichotomic phalanstery that could never be, Christian’s libertarian notions dissipated rapidly with the man finding his end by 1793, either of alcoholism, or its consequences. Death, sometimes violent, took most of the mutineers and Tahitian men as well.

Basically, instead of us finding liberty, justice, and equality, on the Southern Seas, where the Sun is the friend of Man, generations later, we’d find sexual abuse, rampant alcoholism, inbreeding, and a complete failure of the noble ideals that drove Fletcher Christian to throw away the oppressive rule of a petty tyrant.

Freedom, naked freedom can never be the sole objective of any society that doesn’t want to degenerate into a sort of failed phalanstery based on generational moral decrepitude.

If Freedom must be preserved, a set of clear rules must be given to any new society to temper its vocational potential for abuse. One must arrest such tendencies by nipping them in the bud before they take root and rot the generous ideals from within.

Let’s face it, people, perfect freedom is a chimera.

It cannot be arrived at or maintained, nor can Man entertain the illusion that it is morally ok to commune with nature, when in essence, doing so condemns people to a life close to that of fauna and flora. And I don’t know about you, folks, but I would rather live my life as God intended me to, as a pluricellular higher mammal on my two feet and not as a nematode squirming in the rain and mud.

And I am pretty sure, that Nature was never meant to be our model in Life. It may be worthy to live in harmony with Nature, but it is not our destiny to literally live in it.

Mankind’s destiny is to protect Nature and never lose touch with it, but our goal is to conquer Space, and adapt to it. To be content with our condition is to stagnate. Stagnation leads to degeneration. And that is a death sentence to society and the individual.

Being a part of our ecosystem should not be interpreted literally because it doesn’t make us better survivalists. It made Fletcher Christian and his bunch a fixture of two islands, until some of their late descendants realized their ancestor’s folly and decided to move on… to Australia, New Zealand and beyond.

You see, that’s how you know perfect freedom is bound to fail. It can only exist in the mind of the idealist. The realist in me takes stock of life’s conditions as they are, and after shedding a tear at his earlier notions, is ready to move on and accept that change is the common denominator ruling us all.